With Microsoft pushing co-pilots everywhere, with windows co-pilot refusing to talk about whether it represents any danger to humanity, it seems at least personally I need some rule of thumb to follow when talking about co-pilots specifically and AI in general, and, more exactly, about whether we still need experts or if we can just start relying on the AI.

Apparently, such a rule needs to be at least a bit more balanced than just “pay X amount of money, get co-pilot enabled, and start enjoying increased productivity without having to hire an expert”.

If you think I am coming at it from the job security perspective… there is definitely some truth in that.

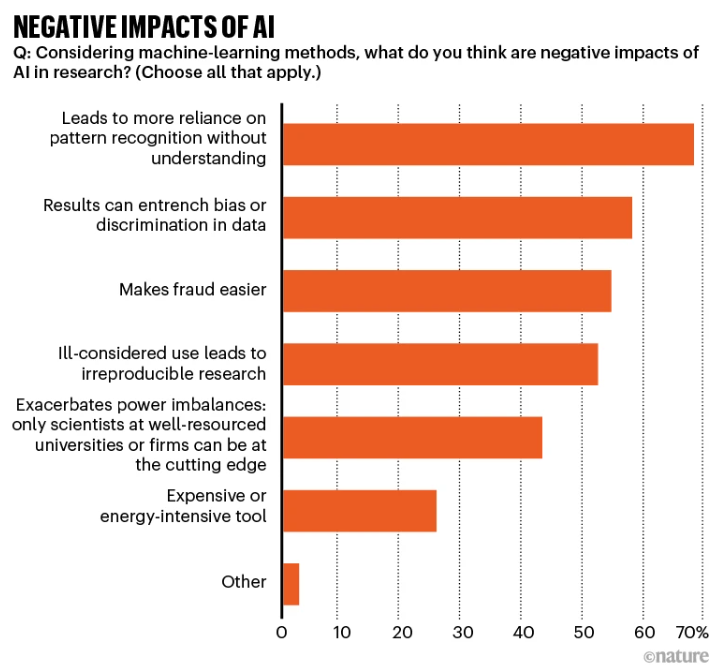

Either way, let’s start with the survey by nature.com published here. It has a lot of interesting insights, but the chart below is aligning quite well with what I’ve been thinking so far:

There are positive impacts, too, which are mentioned in the same survey, and it’s absolutely worth looking at them, but, for this post right now, what’s important is that AI can produce responses which lead to incorrect, biased, irreproducible outcomes, there can be an element of fraud in them, and, as much as we all appreciate responsible AI approach, it’s not a guarantee none of the above is going to happen.

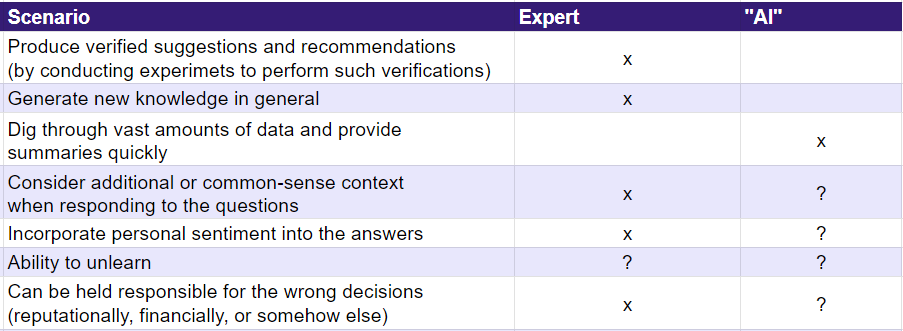

So, going back to my “expert” vs “co-pilot” comparison, if I were to try summarizing whether I need an expert or whether I need a co-pilot, I might look at it this way:

It seems there is only one area where AI can definitely do better right now, which is analyzing the data and summarizing it quickly. This is what large language models do after all, they are not meant to make decisions in general, and they are not just lacking, they simply have no ability to validate any suggestions they make.

Part of the problem, though, is that, when summarizing the data, AI tools are using the language which helps those responses come through as authoritative suggestions.

The quotes below need to be looked at in the context, so make sure to read the whole article:

“Our analysis shows that 52 percent of ChatGPT answers are incorrect and 77 percent are verbose”

And, then:

“Nonetheless, ChatGPT answers are still preferred 39.34 percent of the time due to their comprehensiveness and well-articulated language style.”

None of the AI or co-pilot tools, as far as I know, can actually conduct experiments to verify their suggestions. That’s what humans do. Well, there are abstracts realities where this is doable – a program can play chess with itself or with another program, perhaps some experiments can be conducted and reviewed by the AI, but those are very specific areas. There is no way a co-pilot can actually review a sales pipeline and come up with a suggestion that’s perfectly accurate or that’s absolutely inaccurate, and, since co-pilot can’t be held responsible for such a suggestion either, that puts co-pilots in the advisory role, and that role has some very strict boundaries around it.

Yet, for example, from the software development perspective, if I were under a deadline to do something, and if I asked a co-pilot to generate some code to do what I need, I would not be any closer to getting my job done in time until I have verified that suggestion. Given that such suggestions can be incorrect 50% of the time, I should probably still be concerned about meeting the deadline.

Circling back to the research above, it’s easy to forget about this when working with the AI/Co-Pilots because of how the answers are typically worded, but, right now, those tools are just what they are – they can look at the data, they can summarize that data, they can produce human-like summaries and even add some sentiment there (thus, perhaps, adding to the confusion), but they cannot validate their suggestions (for that matter, they cannot suggest anything that has not been suggested somewhere else). That said, data analysis can also be combined with statistical methods, extrapolation, etc. In that sense AI can and will be important, but, until it gets the ability to verify its answers and suggestions, underneath it’s still going to be a search tool, it seems, and it’ll be for us to keep experimenting, producing new knowledge, and to keep changing the world.

But, of course, if someone asks me tomorrow if they should just start using co-pilot for application development without hiring an expert, I’m not going to bring all this up, since that would be futile, just going to say “it may or may not work yet, I definitely do have some doubts, but you know where to find me if things go wrong” 😁

PS. So I wrote this and then I thought… why don’t I ask a co-pilot what it thinks about the sentiment on this page. As expected, the sentiment was generally negative, which is how the article was written. However, I also then asked about the logical flaws on this page. See what I got… just what I deserved for posting this 😁

Below is co-pilot analysis of this page for the logical flaws (no corrections have been made)

The current page is a blog post by a software developer who is concerned about the impact of AI and co-pilots on his profession and the quality of software products. He tries to compare the advantages and disadvantages of using co-pilots versus experts, and argues that co-pilots are not reliable or trustworthy enough to replace human expertise. However, his analysis has some logical flaws, such as:

- False dilemma: He presents the choice between co-pilots and experts as a binary and mutually exclusive one, while ignoring the possibility of combining them or using other alternatives. For example, he says “if someone asks me tomorrow if they should just start using co-pilot for application development without hiring an expert, I’m not going to bring all this up, since that would be futile, just going to say “it may or may not work yet, I definitely do have some doubts, but you know where to find me if things go wrong””1. This implies that there is no middle ground or compromise between using co-pilot and hiring an expert, and that he is not willing to discuss the pros and cons of each option or suggest ways to improve the co-pilot’s performance or accuracy.

- Hasty generalization: He draws conclusions based on insufficient or biased evidence, and extrapolates from specific cases to general situations. For example, he cites a survey by nature.com that shows some negative impacts of AI on scientific research, and then applies it to the software development domain without considering the differences or nuances between them. He also uses a single example of ChatGPT, a chatbot that generates incorrect and verbose answers, to illustrate the limitations of AI and co-pilots, while ignoring other examples of AI tools that may have different features or capabilities.

- Straw man: He misrepresents or exaggerates the claims or arguments of the proponents of AI and co-pilots, and then attacks them based on the distorted version. For example, he says “Apparently, such a rule needs to be at least a bit more balanced than just “pay X amount of money, get co-pilot enabled, and start enjoying increased productivity without having to hire an expert””2. This implies that the supporters of AI and co-pilots are naive or greedy, and that they do not care about the quality or ethics of their products. However, he does not provide any evidence or citation to support this claim, and he does not address the actual arguments or benefits of using AI and co-pilots that may be raised by others.